?

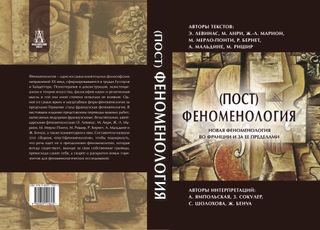

(Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами

M. :

Академический проект, 2014.

Yampolskaya A., Шолохова С. А., Сокулер З. А., Бенуа Ж., Ришир М., Марион Ж., Анри М., Левинас Э., Бернет Р., Мерло-Понти М., Мальдине А., Detistova A., Стрелков В. И., Chernavin G., Yudin G.

Under the general editorship: Yampolskaya A., С. А. Шолохова

Translator: Detistova A., В. В. Земскова, В. И. Стрелков, Chernavin G., С. А. Шолохова, Yudin G., Yampolskaya A.

Compiler: Yampolskaya A., С. А. Шолохова

Chapters

Yampolskaya A., В кн.: (Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами. М.: Академический проект, 2014. С. 11–17.

Предисловие к переводу статьи Э. Левинаса: краткий обзор жизни и творчества, место данной работы в его наследии, анализ данной работы, методологические принципы перевода. ...

Added: October 7, 2014

Yampolskaya A., В кн.: (Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами. М.: Академический проект, 2014. С. 229–240.

В статье анализируется, каким именно образом во французской феноменологии отрицательно определенное понятие пассивности было заменено положительно определенным понятием аффективности и оценивается методический выигрыш от данной замены. Это расширенная и дополненная версия более ранней статьи, вышедшей в "Вопросах философии" в 2013 году. ...

Added: October 7, 2014

Yampolskaya A., Шолохова С. А., В кн.: (Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами. М.: Академический проект, 2014. С. 3–8.

Некоторые современные авторы называют последнюю волну феноме- нологии «постфеноменологией», но мы предпочитаем написание «(пост) феноменология», чтобы подчеркнуть, что (пост)феноменология не подра- зумевает отрицание феноменологии, которая всегда существует, выходя за свои собственные границы, превосходя самое себя. Другими словами, (пост)феноменология гораздо ближе к феноменологии, чем постструкту- рализм к структурализму или постмодернизм к модернизму: пост- в дан- ном ...

Added: October 7, 2014

Yampolskaya A., В кн.: (Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами. М.: Академический проект, 2014. С. 39–42.

Предисловие к переводу статьи М. Анри. Общий обзор жизни и наследия Анри, анализ его вклада в "теологический поворот" французской феноменологии, основные идеи "феноменологии жизни", методологические замечания к переводу, анализ терминологии Анри сравнительно с терминологией А.Мальдине. ...

Added: October 7, 2014

Richir M., В кн.: (Пост)феноменология: новая феноменология во Франции и за ее пределами. М.: Академический проект, 2014. Гл. 15 С. 209–228.

Richir M. Sur l’inconscient phénoménologique: Épochè , clignotement et réduction phénoménologiques // L’art du comprendre. №8. Paris: Vrin, 1999. P. 116–131 ...

Added: November 24, 2014

Research target:

Philosophy, Ethics, and Religious Studies

Priority areas:

humanitarian

Language:

Russian

Veretennikov A., М.: Изд-во РГГУ, 2019.

В пятый выпуск Ежегодника по феноменологической фи- лософии вошли статьи, посвященные важнейшим феноменоло- гическим темам: событие, мир, интерсубъективность. В основе выпуска – материалы конференций, проведенных философским факультетом РГГУ в 2018 году: «От бытия к событию: пути пост- метафизического мышления» и «Алешинские чтения 2018: Ин- терсубъективность, коммуникация, солидарность». Кроме этого, в номере опубликованы русские переводы статей ...

Added: April 30, 2020

Pavlov I., Философия. Журнал Высшей школы экономики 2018 Т. II № 4 С. 51–89

This paper examines the conceptual transformations of Martin Heidegger’s phenomenology of death in Vladimir Bibikhin’s philosophy. For this purpose, the author analyzes Bibikhin’s phenomenology of death in the context of the ontology of time worked out in Bibikhin’s lectures “(It’s) Time.” The key difference between Bibikhin’s ontology and the one from “Being and Time” is ...

Added: January 3, 2019

Ugleva A. V., Философские науки 2010 № 7 С. 40–49

Статья является введением в творчество малоизвестного в России выдающегося современного французского философа-феноменолога и теолога Жана-Люка Мариона, с именем которого связан «теологический поворот во французской феноменологии». Она предваряет публикацию перевода статьи Мариона «Некоторые правила в истории философии», поэтому акцент в ней сделан на историко-философских и теологических исследованиях французского мыслителя и на значении феноменологического метода для его ...

Added: October 12, 2012

Ryabushkina T., Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: Философия 2014 Т. 12 № 4 С. 24–30

The author argues that the classical method of transcendence of the experience bases on temporality and substantiality – the structures that are found by the way of reflection. In classical theory the basis of the experience lies beyond the world of objects. Phenomenologists deny that decision because of its formal character. For Sartre self-consciousness is ...

Added: December 6, 2014

Rutkevich A. M., Вопросы философии 2019 № 12 С. 118–131

The article holds the idea that for A. Kojève during his lecture course «Introduction

to Hegel's Reading» the central figure of the course was «Gestalt

» of the Intellectual. The author of the article emphasizes: the beginning

of the transition from Master–Slave relationship to the bourgeois

world, Kojève sees in times of the late Roman Empire, and with the ...

Added: December 18, 2019

Glebov O., Гуманитарный научный вестник 2019 № 1 С. 17–22

The article is devoted to the problem of the genesis of cultural history of I. Kant. The author "fills the gaps" of Kant's theory based on the data of theories of J. Feibleman and B. Malinovsky. The work also uses the methodology of phenomenology. The object of study is the source of culture, and the ...

Added: March 2, 2020

Ischenko N. I., Антиномии 2018 Т. 18 № 3 С. 27–46

The subject of this article is Heidegger's existentially-ontological consideration of human being (Dasein) as the transcending structure. This article proves the conclusion that the interpretation of Heidegger's intentional consciousness as "transcendence"

means going beyond Husserl's phenomenology. Consequently, raising an issue of intentionality as a specific kind of Being (rather than cognition) Heidegger in contrast with Husserl ...

Added: October 21, 2018

Chernavin G., Horizon. Феноменологические исследования 2013 Т. 2 № 1 С. 28–47

In this paper we treat the problematic of immanent teleology of experience in the boundaries of transcendental phenomenology, including problems such as the accomplishment of intention, adequate evidence, and implications of reason in experience. We bring special attention to the thematic of the Thing, which we treat as a “regulative idea” or as a τέλος. ...

Added: October 14, 2014

Chernavin G., Annales de Phénoménologie 2015 No. 14 P. 97–120

The article discusses the flexible or mouveable architectonics of phenomenological philosophy. The special attention is given to the problems of "Sinnbildung" and "Urstiftung". The phenomenology is considered to be not a philosophical system, but an open research project. ...

Added: April 8, 2015

Chernavin G., Amiens: Association pour la Promotion de la Phénoménologie, 2014.

Cet ouvrage vise à déterminer la manière de travailler qui est propre à la philosophie phénoménologique et à la montrer à l’œuvre. Il s’agit pour cela de définir le changement phénoménologique d’attitude comme « dé-limitation » de la vie de la conscience et la méthode phénoménologique comme « enrichissement mobile de sens », pour apercevoir ...

Added: November 12, 2014

Chernavin G., Interpretationes. Studia philosophica europeanea 2014 Vol. 1 No. 2 P. 85–98

...

Added: November 13, 2014

Kirsberg I.W., Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 2019 Vol. 18 No. 52 P. 142–155

This paper provides a foundation for a form of phenomenology, namely

phenomenological, that rejects the traditional phenomenology of religion in order to

provide a cognitive and non-theological discipline in the study of religion. Proposed

amendments to phenomenology are based on the ideas of E. Husserl. The simultaneous

strict distinction and necessary cooperation between facts and phenomena provided by the

impurity ...

Added: February 24, 2019

Laurukhin A., Вестник Томского государственного университета. Философия. Социология. Политология 2014 № 4 (28) С. 318–329

The article examines Husserl project of the renovation of European cultural mankind in context of the genesis of Husserl’s practical philosophy, existential motivations for the emergence of the idea of renovation (Erneuerung) and in perspective of its adaptations to the contemporary. The key point of the article – Husserl’s thesis about internationalization through the phenomenological ...

Added: November 11, 2014

Ryabushkina T., Антиномии 2015 Т. 15 № 1 С. 28–44

The idea of pre-reflective consciousness arises in response to difficulties that occur in the process of searching for the foundation of the unity of our conscious experience. The basis of the experience can not be found in the experience and lies beyond the world of objects. Can we distinguish a single classical way of transcendence? ...

Added: March 14, 2015

Berlin, Brux., Oxford, Wien, Frankfurt am Main, NY, Bern: Peter Lang, 2014.

Cet ouvrage cible la pratique qui est solidaire de la fondation de la connaissance réalisée par la phénoménologie, en voyant dans cette pratique la condition même de la formulation positive de son projet. Dans cette perspective, la critique sociale et la psychopathologie sont notamment les deux champs pratiques où la phénoménologie se trouve investie, par-delà ...

Added: November 13, 2014

Ryabushkina T., Антиномии 2017 Т. 17 № 4 С. 7–23

The claim that human understanding is grounded in receptivity of mind-independent reality, despite its historical anteriority and accordance with intuition of ordinary consciousness, becomes invalid in the process of development of phenomenological thought. The reason for denial of receptivity is a lack of conformity between separate sense data and concepts as involving unifying functions. An ...

Added: June 8, 2017

Финк О., Логос 2016 Т. 26 № 110 С. 47–60

In his work "Critiquing Husserl: Elements", Eugen Fink reviews the main hurdles encountered by phenomenological research in philosophy. Among these hurdles he lists the interweaving between moments of description, analysis and speculation; the outer-philosophical presuppositions conficting with the claim of presuppositionlessness; the non-thought relation to the philosophical tradition; contradictions between the philosophical project and the ...

Added: October 15, 2016

Malinkin A. N., Вопросы философии 2015 № 11 С. 175–186

Two fundamental problems of the methodology of M. Scheler and K. Mannheim are in focus of this comparative analysis: the one of the rationals of a new sociocentric thinking which is represented in the sociology of knowledge, the another of the objectivity of cognition which is connected with the fending off the threat of the ...

Added: March 3, 2016

Laurukhin A., Мысль: Журнал Петербургского философского общества 2011 № 11 С. 32–51

В статье дан систематический сравнительный анализ философских концепций Э. Гуссерля, Ф. Брентано и представителей школы брентанистов. Критически переосмысляя попытку инкорпорировать феноменологический проект Гуссерля в концепцию Брентано и брентанистов, автор выявляет принципиальные методологические различия двух направлений и показывает формы проявления этих различий через анализ феноменов восприятия, идеации, представления, интенциональных предметов. Проделанный анализ позволяет прояснить вопрос о ...

Added: November 10, 2014

Miroshnichenko M., Философские науки 2020 Т. 63 № 4 С. 46–63

The paper is dedicated to the reconstruction of Alexander Piatigorsky’s observational philosophy within the context of the confrontation between two versions of the transcendental project of man-in-the-world. The first project accentuates the invariant functional organization of cognitive systems by abstracting from bodily, affective and phenomenological realization of this realization. On the contrary, the second project ...

Added: January 26, 2020

Kirsberg I. V., Философия и культура 2012 № 11 С. 29–38

В первой части статьи обосновано понимание богословия как не науки: по феноменологически выявляемым особенностям чувства в отличие от мышления показано ценностное, а не познавательное качество богословия. По особенностям взаимодействия чувства и мышления, соответственно с различением видов соподчинения ценности и знания, показана неоднородность богословия как дисциплины – с преобладанием ценностного. Таким же образом предусмотрено религиоведение – ...

Added: January 31, 2013

Chernavin G., Annales de Phénoménologie 2016 No. 15 P. 55–63

The article provides the analysis of the motive of the profound incomprehensibility of the doxa, solidified in the form of the obvious, by Edmund Husserl and Eugen Fink. The discussion with the philsophy of Martin Heidegger is also provided. The article compares the phenomenological method with the technique of "Er-staunen" (estrangement). The general overview of ...

Added: October 1, 2015

Miroshnichenko M., Russian Journal of Philosophical Sciences (Filosofskie nauki) 2020 Vol. 63 No. 4 P. 46–63

The paper is dedicated to the reconstruction of Alexander Piatigorsky’s observational philosophy within the context of the confrontation between two versions of the transcendental project of man-in-the-world. The first project accentuates the invariant functional organization of cognitive systems by abstracting from bodily, affective and phenomenological realization of this organization. On the contrary, the second project ...

Added: June 24, 2020

Даль Э., Гиргель Д., Наливайко И. et al., В: Логвінаў, 2015.

Издание представляет собой авторизированный перевод сборника Phenomenology of Everyday Life белорусско-норвежского коллектива авторов, вышедшего на английском языке в Осло в 2014г. В сборнике с различных дисциплинарных точек зрения рассматриваются теоретические и практические аспекты изучения феноменологии повседневности (спорт, фотография, онлайн-игры, театр и др.). ...

Added: November 22, 2015