?

Как звали думного дьяка Ивана Елеазаровича Цыплятева (из истории имянаречения XVI столетия)

С. 387–396.

Uspenskij F.

Keywords: культ святыхимянаречениесветская христианская двуименностьмонастырские вкладывкладные и богослужебные книги

Publication based on the results of:

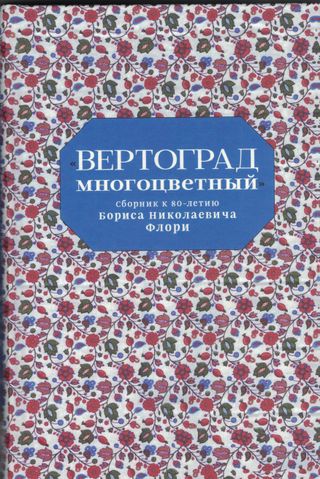

In book

Ivanov S. A. М.: Издательство "Индрик", 2018.

Евдокимова Е. С., Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Вопросы ономастики 2025 № 3 С. 39–83

The study is devoted to the representation of name days in a poorly studied and largely unpublished corpus of sources – the supplies books of the Patriarchal Court. As will be shown in the article, these materials are a promising source for solving various onomastic problems. The pages of the supplies books recorded visits from ...

Added: July 18, 2025

Зенкова М. А., Электронный научно-образовательный журнал "История" 2025 Т. 16 № 2(148)

The author examines the practice of veneration of St. Clement of Rome within the Western and Eastern Christian churches, as well as in Iceland, where his cult was less widespread. Based on the image of St. Clement in Old Norse literature, it can be concluded that the saint holds a particular role in this society ...

Added: February 12, 2025

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Древнейшие государства Восточной Европы 2024 С. 179–190

Статья посвящена атрибуции восьмиконечного креста-мощевика в серебряном золоченом окладе с чеканными и резными священными изображениями и орнаментами. Согласно вкладной надписи на кресте, он был пожертвован в суздальский Покровский монастырь в 1603/04 г., при этом характер растительного орнамента, мастерство чеканки и подбор драгоценных камней однозначно свидетельствуют о столичном происхождении этого литургического предмета. ...

Added: November 26, 2024

Vinogradov A., Чхаидзе В. Н., Slovĕne 2023 Т. 12 № 2 С. 7–18

The article deals with the question of the Christian name of Rostislav Vladimirovich

the prince of Tmutarakan. The newly found seal of Rostislav Vladimirovich

shows that he bore the Christian name Gabriel (in honour of the

archangel Gabriel), which came to the Rurikids probably from the Bulgarian

Kometopouloi dynasty. The Greek legend on the seal of Rostislav speaks probably

about ...

Added: August 7, 2024

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., В кн.: Порядок и смута. Государство, общество, человек на востоке и западе Европы в Средние века и раннее Новое время: К 85-летию Владислава Дмитриевича Назарова.: Аквилон, 2023. С. 264–275.

Данна работа посвящена именам представителей бюрократической элиты XVI -- первой половины XVII века. Обсуждается, в частности, наличие двух христианских имен в миру у А. Я. Щелкалова, И. Е. Цыплятева, Б. И. Суина, Ф. Н. Апраксина и Н. Н. Новокщенкова, рассматриваются принципы функционирования этих антропонимов, их роль в разных сферах светской и церковной жизни. ...

Added: December 2, 2023

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Вестник сектора древнерусского искусства 2023 № 1 С. 89–94

This work, using as example the telling case of the naming of the member of the Golovin noble family, describes the general principles of the selection of two secular Christian names for the same person and discusses the possibility of the interdependence of these two an- throponyms. This work demonstrates to what extent the names ...

Added: December 2, 2023

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Авдеев А. Г., Ипатьевский вестник 2023 № 2 С. 161–173

The paper for the first time publishes a white stone tombstone from the Godunov family tomb in the Holy Trinity Ipatiev Monastery (Kostroma). The restored text of the epitaph suggests that it indicates a representative of the Godunov family, the son of Iosif (Asan) Dmitrievich Godunov, who had two secular christian names — the baptismal ...

Added: December 2, 2023

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Древняя Русь. Вопросы медиевистики 2023 № 4 С. 86–99

В работе обсуждается одна из переломных точек в истории московского правящего дома, да и всей близящейся к закату династии Рюриковичей, – речь идет о пострижении в монашество княгини Евфросинии Андреевны Ста- рицкой, матери Владимира Старицкого, внука Ивана III. В широком контексте своеобразного языка имен и дат, достигшего наивысшего расцвета в эпоху Ивана Грозного, рассматривается символическая ...

Added: December 1, 2023

Kuksa T., Традиционная культура 2023 Т. 24 № 3 С. 177–183

Review of: Golubeva L.V., Kupriyanova S.O. (comp.). Maternity in the Soviet Village: Rituals, Discourses, Practices: In 2 vols. Vol. 1: Research. Vol. 2: Fragments of Interviews. Ed. by S.B. Adonyeva. St. Petersburg: The Propp Center, 2022. 320 p., 896 p. ...

Added: October 12, 2023

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., СПб.: Евразия, 2022.

День рождения и имя собственное — едва ли не самый очевидный зачин для рассказа о судьбе того или

иного исторического лица. Однако обратившись к эпохе, которую принято называть Смутным временем, мы вдруг обнаруживаем, что далеко не всегда эти имена и значимые даты нам известны, даже если речь идет о правителях, не один год занимавших московский престол. Филологическое расследование ...

Added: June 2, 2022

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Scando-Slavica 2022 Т. 68 № 1 С. 157–174

In the medieval Russian anthroponymic system, a lay person could have several names simultaneously. The public name of a person was not always their baptismal forename. Also, recent research has shown that the full sets of

personal names of some of the Russian tsars and their relatives are still unknown to us, not to mention the names of the ...

Added: June 2, 2022

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Die Welt der Slaven. Internationale Halbjahresschrift für Slavistik 2022 Т. 67 № 1 С. 68–90

It is widely accepted in academic literature that, due to the marriages of Peter the Great and his brother Ivan V, each of their respective fathers-in-law received the same new name of Feodor. he present work offers a different perspective on this onomastic event — it is considered in a broader context of the evolution of the ...

Added: April 4, 2022

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Русская речь 2021 № 6 С. 77–97

The paper dwells on various onomastic means that ensured family unity within a generation in Medieval Rus’, highlighting, fi rst and foremost, the unity between brothers. The important research tools are the history

of personal patronal saints cult and the fact that many Christians of the pre-Petrine time uses to have two names: a baptismal one, as well as ...

Added: December 22, 2021

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., В кн.: Dísablót. Сборник статей коллег и учеников к юбилею Елены Александровны Мельниковой.: М.: Квадрига, 2021. С. 267–274.

This article aims to shed a new light on the figure of the Novgorodian posadnik Miroslav Gyuryatinich; primaraly, on his engagments and political activity outside Novgorod. The authors touch upon the problem of the repetition of names among the Rus elite of the 11th-12th centuries and express some considerations about the supra-regional ties of the ...

Added: December 1, 2021

Litvina A., Uspenskij F., Slovĕne 2021 Т. 10 № 1 С. 94–112

The present paper offers a rethinking of inscriptions and images on the famous artifact known as “Prince Ivan Khvorostinin’s reliquary”. We are interested both in the texts inscribed directly on various parts of this objects and those potentially linked with some of its elements. Contrary to the widely accepted opinion, the article suggests seeing this ...

Added: October 28, 2021